Financial Loss Aversion Illusion

Published:

This is a brief non-technical summary of my forthcoming article in the Review of Finance.

Most people dislike losses much more than they like gains of equal size, a feature of human preferences known as loss aversion. It has been frequently documented in psychology and economics, with the conclusion that losses loom larger than gains by a factor of about two. In finance, loss aversion is suggested to explain, for instance, the equity premium puzzle (“Why are stock returns so high?”) and stock market participation (“Why do so few people invest in stocks?”).

In the evaluation of gains and losses, one has to distinguish between anticipated and experienced outcomes. Most scientific experiments use gambles or lotteries which focus on the trade-off between anticipated gains and losses. However, this implies that people are able to forecast the hedonic impact of gains and losses with great accuracy. In contrast, recent evidence suggests that people’s ability to cope with losses is much better than they predict.

Using a unique dataset, I tests this proposition in the financial domain. In a panel survey of retail investors from a large bank in the UK, participants state how they feel about anticipated and experienced returns in their investment portfolios. In a time period of frequent losses and gains in the stock market (2008-2010), I examine how their ratings relate to the magnitude of portfolio gains and losses.

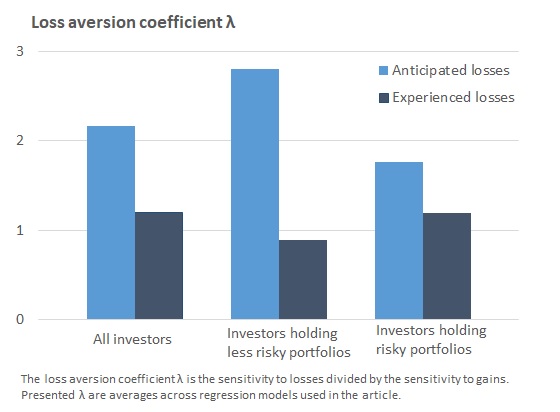

The results demonstrate that loss aversion is strong for anticipated outcomes, for which I obtain a loss aversion coefficient of about 2.2. This means that investors react twice as much to negative expected returns as compared to positive expected returns. However, when evaluating experienced returns, the loss aversion coefficient decreases to about 1.2. Investors are not more sensitive to losses than to gains when they are reflecting about their past portfolio performance. The loss aversion they show ex ante seems to be partly or fully an affective forecasting error.

The findings have practical implications for investing behavior. While loss aversion is a legitimate part of people’s preferences, the documented financial loss aversion illusion represents an inconsistency in how a loss is viewed at different points in time. If investors systematically overestimate their personal loss aversion when thinking about financial outcomes, their investment decisions will differ from what is justified by their actual experiences. In particular, they will invest in less risky assets than would be optimal from an ex post perspective and will avoid potential losses unless they receive a substantial compensation. Indeed, investors with less risky portfolios in terms of volatility or assets are found to be more loss averse. However, this higher loss aversion is not backed by their loss experience as they do not react differently to losses compared to investors who bear higher portfolio risk.